Sustaining ALPA's Legacy in Accident Investigation

Twenty participants, including ALPA Air Safety Organization (ASO) volunteers from nine of the Association’s U.S. and Canadian pilot groups, gathered in Cleveland, Ohio, on August 12–15 to take part in the union’s Accident Investigation Course. The training prepares pilot safety representatives to serve as ALPA accident investigators and party coordinators or observers during accident and incident investigations.

The course introduces participants to the investigative processes of the NTSB and the Transportation Safety Board (TSB) of Canada and also reviews how accidents in foreign countries follow the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) process and how jurisdiction for an investigation is determined. Attendees also learned how the Association works in cooperation with investigative authorities. The goal is to prepare pilots to take part in an accident investigation, providing them with both procedural and technical knowledge as well as an appreciation for the critical role they play as line-pilot representatives.

Since its founding in 1931, ALPA has placed aviation safety at the core of its mission. The Association’s early advocacy was instrumental in creating independent investigatory authorities such as the NTSB in the United States and the TSB in Canada. Over the decades, ALPA volunteers have become trusted partners in the investigative process, providing operational expertise that helps ensure all relevant factors are considered and that lessons learned are translated into safety recommendations and improvements.

Whenever an accident occurs, investigative authorities depend on the cooperation and expertise of many stakeholders—airframe and engine manufacturers, regulators, operators, and pilot representatives among them. Association investigators can be dispatched at a moment’s notice, often under difficult circumstances. They must be ready to represent both the union and the line-pilot perspective with professionalism and technical competence.

“We hold these courses to get you up to speed and provide you with an understanding of the process so that you can act as an ALPA representative on an investigation,” said Capt. Jeff Mee (United), the ASO’s Accident Analysis & Prevention Group chair who serves as the course director. “It’s also an opportunity for us to share some of our experiences. And with so much turnover at some of our pilot groups, we do our best to get our members into these courses to maintain a trained pool of volunteers at every ALPA master executive council.”

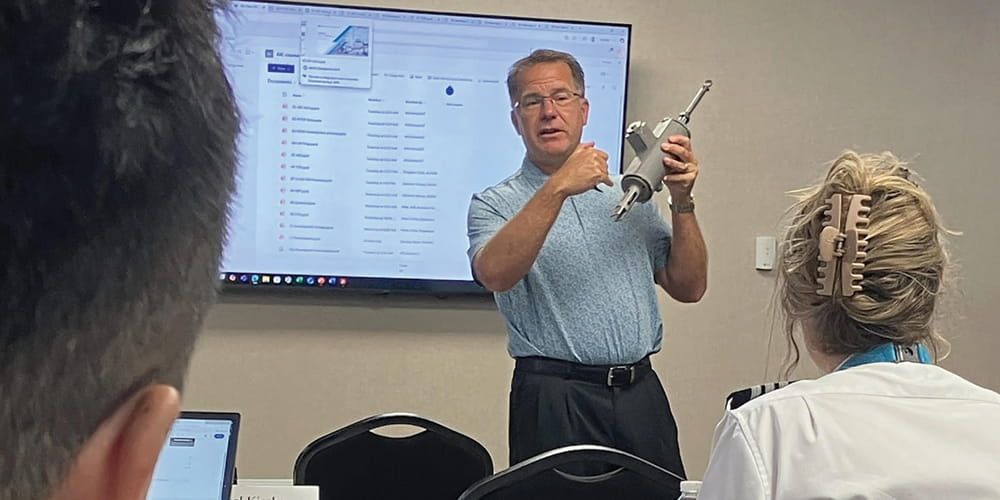

The course is taught by a highly experienced team of the Association’s accident investigators. In addition to Mee, instructors at the recent training event in Cleveland included Capt. Matt Gorshe (Spirit), chief accident investigator for his pilot group who also serves as an ASO regional airport safety coordinator; Capt. Chris Duggan (Air Canada); and F/O Stacey Jackson (WestJet), the ASO Training Programs coordinator. All these instructors currently serve on ALPA’s Accident Investigation Board, which includes additional experienced accident investigators from the union’s U.S. and Canadian pilot groups. Chris Heck, lead engineer in ALPA’s Engineering & Air Safety Department, also served as an instructor, providing technical expertise and staff perspective. Together, they represent decades of cumulative experience across numerous investigations.

Over the four days of training, participants worked through an ambitious syllabus. They received a detailed overview of how the NTSB and the TSB conduct accident and incident investigations and how ICAO Annex 13 investigations are structured when responding to an international accident. Instructors also discussed the strict prohibitions on sharing information with anyone outside of an investigation. Details gathered by investigators during an inquiry must never be discussed publicly or speculated on, even within their own pilot group.

The course also emphasized the practical realities of on-scene participation. Attendees were cautioned about crash site hazards, including unstable wreckage, fire risks, HAZMAT, and bloodborne pathogens—dangers they might encounter during the field phase of an investigation. Instruction also focused on occupational safety and health mandates for bloodborne pathogen precautions and guidance on the use of personal protective equipment.

“You may have sharp metal, unstable surfaces, unknown household and commercial goods in passenger luggage, and objects or materials that are under pressure,” Jackson remarked. “Aircraft are full of flammable liquids and gasses, so treat everything with kid gloves and proceed with caution.”

The training also introduced many of the specialized technical groups that form the backbone of accident investigations, which can include aircraft systems, operations, air traffic control, structures, powerplants, flight data recorder, cockpit voice recorder, meteorology, metallurgy, aircraft performance, and human performance. Every investigation is different, and the circumstances surrounding the accident or incident will dictate which technical groups are necessary for a thorough investigation. Participants learned how investigative authorities assign pilots to technical groups as subject-matter experts where their operational knowledge of aircraft and procedures can be invaluable.

Instructors discussed the need for disciplined documentation and the importance of maintaining clear and detailed field notes, stressing that observations made by investigators are a critical part of the investigation. Photography is part of that documentation, but observations must still be described in writing. When examining a crash site or wreckage, descriptions must be factual, accurate, and free of assumptions. And the careful use of language is critical. The distinctions between something described as “dented,” “nicked,” “pitted,” or “gauged” can be subtle and carry different meanings for the investigation, so precise terminology language is essential.

“It can be extremely difficult to find the words to describe what we see visually when writing up field notes,” said Gorshe. “As pilots, we know exactly what the nomenclature is for the switches on the flight deck. That’s our language. But it’s more challenging when describing something that we’re less familiar with. That’s why there are experts from other disciplines serving on the various technical groups who can help with that documentation.”

Participants also heard from Nathan Williams, a Boeing air safety investigator. His presentation provided insight into how aircraft manufacturers approach accident investigations, helping attendees better understand the collaborative process that brings regulators, operators, manufacturers, and labor representatives together in pursuit of safety.

“If you participate in an investigation,” Williams noted, “you’ll get to see a big team working together, entirely with the goal of improving aviation safety and trying to understand what happened—not to attribute blame, but to figure out what can be improved.”

The course also covered the later stages of an investigation, including NTSB technical reviews, public hearings, and the development of submissions. Jackson and Duggan spoke specifically about the Confidential Draft Report (CDR) process, which is how input is provided to the draft report in a Canadian investigation. Surviving crewmembers or their next of kin are usually designated as reviewers of the CDR and can seek guidance from the Association in making comments.

“We’re there to help, if they want the help,” said Duggan. “We can brief them on what to expect. And if they want assistance, it’s absolutely within their rights to ask ALPA for support.”

It’s also important that the Association’s accident investigators be familiar with the ways that individuals respond in the wake of a tragic accident and what resources are available to help support them. In the aftermath of an event, families, colleagues, and communities are often deeply affected. ALPA’s Critical Incident Response Program is closely coordinated with accident investigation activities to ensure that flight and cabin crews, airline personnel, and the investigators themselves receive the support they need as the investigation unfolds.

ALPA’s Accident Investigation Course is the initial course that volunteers must take to represent the union on an accident investigation. It serves as a prerequisite for ALPA’s Advanced Accident Investigation Course, which is held at the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks. The advanced course places participants in a full-scale accident simulation, giving them hands-on experience as field investigators. Together, these courses build the skills and confidence that volunteers need to operate effectively in real-world investigations.

While ALPA’s Accident Investigation Course is offered several times during the year at various locations throughout the United States and Canada, the Advanced Accident Investigation Course always takes place in Grand Forks. The next advanced course is scheduled for October 20–23, providing graduates of this recent training an opportunity to further develop their understanding of investigative techniques and processes.

Accident investigation is demanding work. It requires precision, patience, and resilience. But it also offers the opportunity to make a lasting difference. Each investigation contributes to a body of knowledge that helps prevent future tragedies and advances the cause of aviation safety, helping to safeguard the air transportation system for generations to come.

This article was originally published in the September 2025 issue of Air Line Pilot.